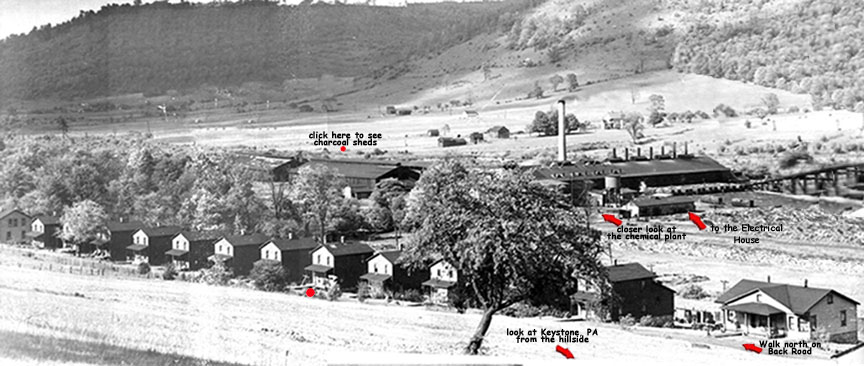

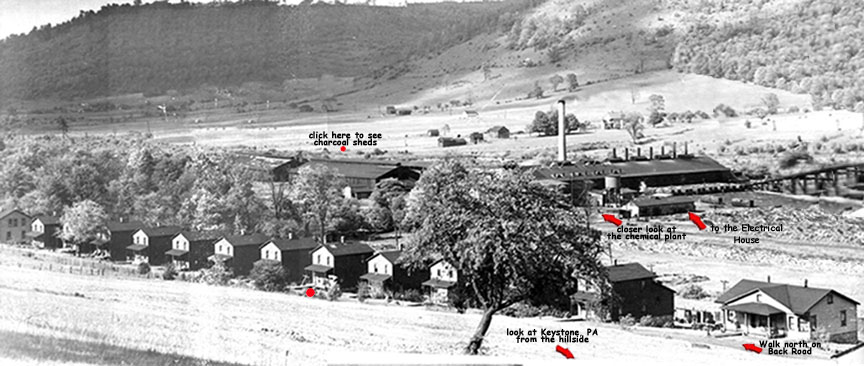

photo credit: Michael Dodge Collection

Welcome

to Keystone, Pennsylvania

The Quinn's last chemical plant!

photo credit: Michael Dodge Collection

Click to see the location in 2004

Keystone,

Pennsylvania, was a mile north of Betula. It was a factory town, which caused

it to vanish when the factory shut down. The largest building was the

chemical factory, which you see in the distance.The building at the left was

a warehouse where charcoal and acetate was stored. The wood yard stretched for

close to a mile to the right of the picture. This view looks northeast. The

company homes in the foreground are no longer existent and there are few traces

of the chemical company left. The Keystone plant of the Quinns was the last

new chemical plant built in Pennsylvania, and the most efficient . Along the

northern border of Pennsylvania between the 1800s and 1950s, there was more

than 70 wood chemical plants. McKean County was the center of the industry.

It was centered here because of the cheap natural gas. These factories converted

logs into charcoal, methanol (wood alcohol), and acetate of lime or acetic acid.

They took the smaller hardwood that lumber mills wouldn't use. The subsequent

development and history of the industry was revolutionized by Martin F. Quinn,

who invented the jumbo retort. The jumbo allowed plant size to rapidly rise

to seventy and ultimately to 140 cord capacity. Pyrometers controlled retort

temperatures, vinegar hydrometers tested the liquor, and color charts controlled

the liming process. By keeping down retort temperatures, alcohol and acid

production was increased and the charcoal was denser. The vinegar hydrometers

saved acid that had been dumped with the tar. Instead of the usual ten

gallons of methanol, they got 10 1/2 gallons; instead of 50 bushels of charcoal

they got 55; and instead of 200 pounds of acetate, they got 265 pounds.

Keystone, Betula, and Norwich were all serviced by the Potato Creek Railroad.

When the Norwich operation closed during 1920 the railroad as well as the remaining

plants were doomed.

WOOD CHEMICAL PLANTS

Along the northern border of Pennsylvania between the

1800s and 1950s, there was once more than 70 wood chemical plants. But

how many people actually know what a wood chemical plant is and why is

it important to us? Well, at one time McKean County was the center of

the industry. It was centered here because of the cheap natural

gas.

These factories converted logs into charcoal, methanol (wood alcohol), and acetate of lime or acetic acid. They took the smaller hardwood that lumber mills wouldn't use.

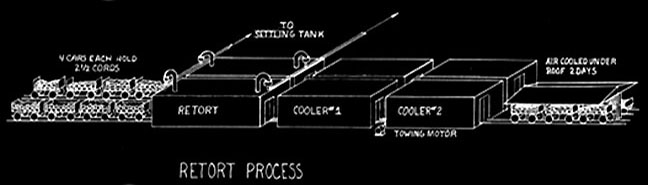

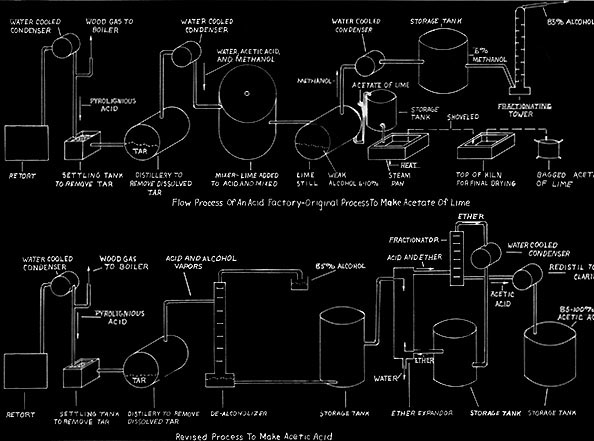

The basic process was to heat , in the absence of oxygen, the wood to a very

high temperature which would drive off its chemicals and turn the remaining

wood to charcoal. The chemicals were treated so as to produce methanol

and acetate of lime. The charcoal was cooled, and most of it subsequently

sold to iron producers.

The Wood Chemical Industry

By 1890 the wood

industry was established and manufacturing patterns set. The plants were

small, with daily capacities of ten to - at most - twenty cords. The subsequent

development and history of the industry was revolutionized by Martin F. Quinn,

who invented the jumbo retort. The jumbo allowed plant size to rapidly

rise to seventy and ultimately to 140 cord capacity in Pennsylvania and even

greater sizes elsewhere.

The material which follows is from Evan Quinn, who was personally involved in

the transition and the ultimate development of acid factories. As the

equipment and the processes are best described by photographs, drawings, and

charts, narrative text will be minimized.

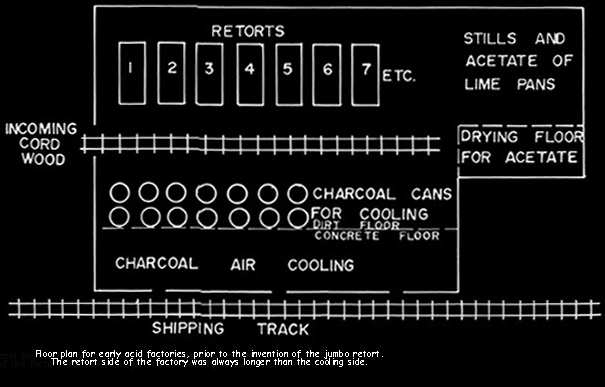

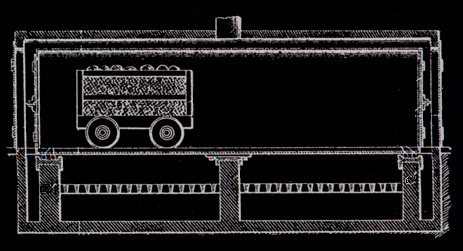

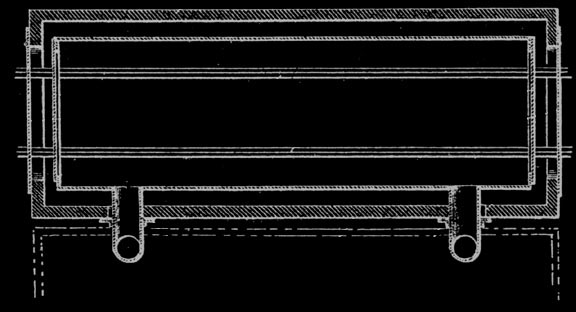

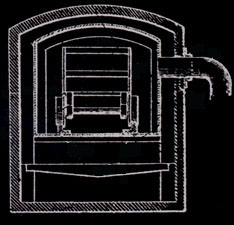

Prior to the invention of the jumbo retort in 1897, the retorts were cylindrical

and held 3/4 cord of wood. They were five feet in diameter and 112 inches long.

Wood stored out of doors was hand loaded onto carts, moved into the building

beside the retorts, hand loaded into the retorts, heated, hand raked into cans

for cooling, and the cans moved to an adjacent cooling area. These cans

were three feet in diameter and four feet deep, air tight, and with a projection

for moving on a two wheel cart.

In the heating of the wood, an interesting change takes place. At about

400 degrees an exothermic reaction occurs which raises the temperature to 600

degrees with no additional heat necessary. The smoke or vapor is poisonous

and contains more than one hundred different chemical - most of which are traces

and not economical to recover. However, as plants became larger, it became

feasible to recover a greater number of the chemicals. Normally only methanol

and acetate of lime were produced, but at Glenfield, NY methyl acetone and buturic

acid were also refined.

Martin Quinn had been involved with acid factories, as they were originally called, for more than a decade when he developed and patented his jumbo retort. The original jumbo retort held four cords of wood, but within a few years reached its optimum ten cord size. The jumbo allowed the steel cars loaded with wood to be rolled into the retort and then into cooling chambers, thereby eliminating more than half of the labor formerly needed. His biggest problem was how to handle expansion and contraction. The retort had to be metal and air tight. It had to be surrounded with a brick housing to serve as insulation. The first jumbos were supported on rollers, but they were not successful because of jamming and all subsequent retorts until Glenfield were hung. To take care of expansion the retorts were supported at their middle and ends. But hanging retorts had a warpage problem. The high heat caused buckling. Every so often every retort had to be forced back into shape. For Glenfield Evan Quinn reverted to the roller support, but of a different design, and thereby did away with excessive warping.

Quinn introduced his jumbo retorts into the Lackawanna Chemical Company plant at Straight. In the same space he doubled output from the former twenty cords to forty and used jumbos, but had only a twenty cord capacity. Following the development of the jumbo retort, further improvements involved the chemical processes. The greatest single change was the development of making acetic acid directly instead of making acetate of lime and shipping it to another company for conversion to acetic acid. This direct process was invented in Germany.

The Baker Chemical Company of New York sold the process to the Quinns and built a plant at Keystone. A large diameter extractor was the heart of the Baker process. Ether was passed up through the extractor, which was full of pebbles, and weak acid liquor came in at the top and passed down. The pebbles broke up their flows so as to intermix the two. The ether and acid then combined and water dropped out thus concentrating the acetic acid. Although the process worked experimentally for Baker, it was a failure at Keystone. The ether went up close to the sides of the extractor and the acid came down the middle. Intermixing was poor.

The Quinns now designed their own extractor, only 24 inches in diameter, and

this was successful. There was no room for the ether and acid to bypass

each other without mixing. The continuous acetic acid process was then

pt into the Tionesta Valley Chemical company's Mayburg plant and later also

at Laquin and Glenfield. After Glenfield closed, its equipment was divided

in half and moved to Morrison, McKean County and Hallton, Elk County.

Although the price for a cord of wood remained constant at $5.00, prices for

the finished products varied considerably. Prior to world War I it varied

between $10.50 and $19.00 per cord. The typical out put from a cord of

wood ws ten gallons of methanol which sold for $0.25 - $0.50 per gallon for

85% alcohol, 200 pounds of acetate of lime (calcium acetate) which sold for

2 1/2 cents - 5 cents a pound, and fifty bushels of charcoal (1000 pounds) which

sold for $0.05 - $0.08 per bushel. The direct acetic acid process make

one hundred pounds of 98% acetic acid per cord and sold for $0.20 per pound.

The acetic acid was the most valuable product. During World War I price

controls allowed the prices to reach $0.50 per gallon for the alcohol, $0.10

per bushel for charcoal, and $0.05 per pound for the calcium acetate.

After price controls were removed alcohol prices soared and profits were tremendous.

One of the reasons for the increase in methanol price was Prohibition.

Some individuals making grain alcohol from molasses continued to sell to bootleggers.

These manufacturers had to prove that they were denaturizing their grain alcohol.

They would buy a tank car of methanol (8,000 gallons) which would denature 80,000

gallons of grain alcohol. They would pay for the methanol and dump it

into the sewer. One of them up in New England for got to empty the Quinn

tank car and returned it still loaded. The Quinns wired the consignee

as to what they wanted done with their methanol, and they advised to ship it

back and invoice them for another 8,000 gallons.

Production varied at different plants. Hard maple and beach made the best

chemical wood. Oak gave high charcoal yield, but was low on methanol and

acid, which were the more valuable products. Compared to the central and

southern portions of Pennsylvania, the northern third of the state had relatively

little oak mixed in with the other, more valuable hardwoods. This factor

plus the abundance of cheap natural gas in the McKean County area caused the

industry to locate along the northern border of Pennsylvania with the greatest

number of plants in McKean County. In 1913 there were 41 plant in Elk

and McKean Counties.

The newer plants also were more efficient than older ones. The Keystone

plant of the Quinns was the last new chemical plant built in Pennsylvania, and

the most efficient. Pyrometers controlled retort temperatures, vinegar

hydrometers tested the liquor, and color charts controlled the liming process.

by keeping down retort temperatures, alcohol and acid production was increased

and the charcoal was denser. The vinegar hydrometers saved acid that had

been dumped with the tar. Instead of the usual ten gallons of methanol,

they got 10 1/2 gallons; instead of 50 bushels of charcoal they got 55; and

instead of 200 pounds of acetate, they got 265 pounds.

The products of the chemical plants were sold through three sales companies.

Charcoal was sold by the Manufacturers Charcoal Company of Bradford. This

company was organized by the charcoal producers with one share of stock being

given for each cord of capacity of a producer. Each chemical company told

manufacturers their production, and as orders were received, the different chemical

companies would be notified to ship so many carloads to designated locations.

Charcoal was important because it contained no sulphur. Sulphur is poisonous

to nickel and chromium so that high grade steels and stainless steel had to

be smelted by charcoal. Huge amounts went to the International Nickel

Company. Premium iron, such as required for boiler tubes, required charcoal

until World War I. Carload after carload went to the Lukens Steel Company

at Coatesville, Pennsylvania. It was also used in making black gun powder.

Dupont, Hercules, and Atlas bought large quantities. Charcoal was also

ground to a fine powder for use in filter beds, gas masks, and whiskey distilleries.

The Wood Products Company of Buffalo had the monopoly on selling methanol.

All wood alcohol was sold to them. About 1910 several of the manufacturers

were unhappy with prices, and so Quinn and several others organized the Manufacturers

Distillers Company at Olean. They built a large plant, but never had to

use it. Wood Products raised the price and leased the empty building.

Prices for acetate of lime were established by the National wood Chemical Manufacturers

Association to which Martin Quinn was an officer. They met monthly in

New York or Buffalo. These meetings were not always harmonious, and Evan

Quinn remembers the wrangling that went on whenever one of the members tried

to make a fast dollar by selling outside the organization. Users were

always trying to break up the combine by offering to buy from a single company

at a higher price when supplies were tight.

But like most good things, there had to be an end sometime. During the

1920s and 1930s other methods were developed for smelting alloy steel, such

as electric furnaces. Black powder usage declined rapidly. Desulphurizing

of petroleum products was developed. Other methods for making acetic acid

and methanol became cheaper. With reducedneeds caused by competing processes

and the Depression, the wood chemical industry faired badly. In Pennsylvania

the last large plant, the Mayburg operation, closed in 1942 when the Sheffield

and Tionesta Railroad, which served it, was torn up and the rails used elsewhere

for the war effort. Smaller plants continued through the war and into

the early 1850s before giving up. Today, near Bradford at Custer City,

the last of the former chemical plants still operates making distillery charcoal.

Facts & graphics gathered from:

Sawmills Among the Derricks, Thomas T. Taber, III, ©1975, Book No. 7 in the series, Logging Railroad Era of Lumbering in Pennsylvania

Keystone, live town, soon

fades from pictureAnother week will finish big chemical plant

The nearby town of Keystone near the head of the Potato creek valley, which for a number of years past has been a busy, properous, McKean county community, is fast nearing the end of its days.

In another week's time the huge chemical factory of the Quinn interests, with which the town came into existence, will have completely exhausted its supply of wood, which up to a year ago was regarded as one of the largest "woodpiles" in the entire world, and work of dismantling the factory will be started in earned.

The Keystone factory and the big chemical plant at Straights, which finished operation several months ago, and being moved to the Adirondack mountain region, some distance from Utica, N. Y., where the Quinn's have a big acreage of woodland.

Most of the houses at Keystone will also be moved to the Adirondack operation where a new town of considerable size will appear on the map as a result of the starting of the combined big chemical plants.