|

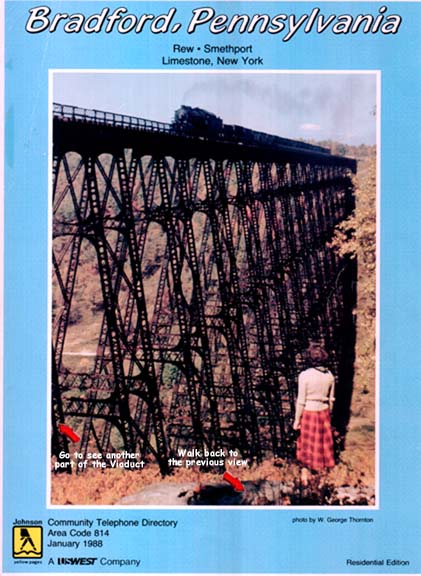

Tracks Across the Sky

To span the valley, the Kinzua

Viaduct had to be the loftiest

Structure of its kind on earth.

By: W. George Thornton

Erie Railroad Magazine, August 1949

Coal, Timber, Oil! Here were the magic words

of a million endeavors in the adventurous and expanding America of the

1880?s. Moving words too for a man like General Thomas L. Kane who

would build his own railroad to break the mountainous isolation of his

vast and rich  domain

high in the Alleghenies of northern Pennsylvania. domain

high in the Alleghenies of northern Pennsylvania.

Pushing southward from the Erie's terminus at Bradford, Kaneís

New York, Lake Erie and Western Railroad and Coal Company line moved up

the steep and heavily wooded slope of the Big Shanty in the great reverse

curve and thence across a high plateau until the valley of the Kinzua Creek

challenged the abilities and dreams of enterprise and engineer. The

water of many and large fishes as the Indians knew the Kinzua lay at the

bottom of a defile 2,000 feet wide and 300 feet deep. To Kane the

Kinzua gave two alternatives. One was the construction of four miles

of tortuous, twisting two percent grade; the other the erection of a railroad

viaduct loftier than any yet built by men. The General investigated

the latter possibility and found his answer in the person of Anthony Bonzano

o the Clarke Reeves Division of the Phoenixville Bridge Company.

?We'll build you a bridge a thousand feet high Bonzano told Kane, if you'll

provide the money The General had the money, and Bonzano, using propositions,

which had proven their worth in similar structures joined with Oliver W.

Barnes, chief engineer of the railroad, in planning the first Kinzua Viaduct.

Construction began May 10, 1882. Just ninety four working days

later a crew of forty men had completed the highest railroad viaduct in

the world. The astonishing feat involved the erection of 3,105,000

pounds of ironwork into a structure 301 feet high and 2,053 feet long.

The work was done without use of scaffolding. A gin pole was used

to erect the first tower. A wooden crane erected at the top of the

top of the first tower was used to place the ironwork of the second tower.

This procedure was repeated until all twenty towers had been raised and

the connecting latticework spans placed.

Stone secured from the nearby hills provided the footings which rose

as high as sixteen feet above the ground and which went down as far as

thirty five feet below the surface John C. Noakes placed the stone work

which was joined to the iron work by one and one half inch bolts, six to

ten feet in length.

Legs of the supporting towers were flanged, wrought iron columns nine

and three quarters inches in diameter spliced at every panel by inside

sleeves. Strengthened by longitudinal and transverse horizontal latticework

struts, the legs were guardrails stiffened by diagonal tie rods in the

vertical, horizontal and transverse planes of each panel. Additional

supporting columns ascended vertically to the fifth story midway between

the legs of the tallest towers. These columns were connected at each

story by a tubular horizontal strut for further stiffness.

The supporting legs sloped inward transversely in the ratio of one to

six. Towers were uniformly nine feet wide at the top. At the

lowest point the tallest tower had a spread of one hundred and three feet.

Each tower had a span of thirty eight and one half feet. Towers were

joined by sixty foot latticework spans. The entire structure was

bolted together save for the prefabricated latticework girders.

The completed viaduct was a swaying structure. From the beginning

it was necessary to restrict the speed of trains to five miles an hour

as even at this speed vibration while not dangerous was unpleasant.

The entire structure was such that even wind pressures would set the viaduct

in motion.

From the beginning the idea has persisted that the original Kinzua Viaduct

was of wooden construction. This erroneous idea perhaps developed

from the fact that the supporting legs were tubular and thus resembled

wooden poles. Likewise, the ties, walkways and guardrails were of

wood and these features of the structure were the most apparent to those

who examined it but casually. Moreover, the wooden guardrails were

of latticework construction and very similar in proportions to the latticework

iron girders.

Fell Thirty Times

Charles P. Stauffer superintended construction and upon completion of the

viaduct took up his residence within the shadow of the structure, remaining

on as the viaduct inspector. Each week he inspected every bolt and

rod and suffered more than thirty falls in the coarse of his work.

He survived one fall of 210 feet while making a test of a fire escape for

skyscrapers for an inventor. Stauffer succumbed following a sixty

foot fall just before the turn of the century and was succeeded by Walter

S. Meserve who was an inspector until the erection of the second Kinzua

Viaduct or Bridge as it is often called.

Two years after Stauffer became the bridge inspector he became the father

of a son to whom the name Andrew Kinzua was given. ?Andy? Stauffer,

faced with the problem of supporting a family of six following his father's

demise went to work as a water boy when the original viaduct was replaced

with a stronger structure in 1900. Subsequently, ?Andy? served the

Erie for forty eight years during which time he rose from water boy to

painter; from painter to bridge inspector. In 1926 he became general

bridge inspector for the railroad, a position that he held until his retirement

in 1948. Today he lives in Jamestown, N.Y.

The original Kinzua Viaduct was advertisement as the Eighth Wonder of

the World. People from all over civilized world were attracted to

the site. Dollar excursions were run on Sundays from the cities as

far distance as Buffalo and Pittsburgh. It was not unusual for six

or eight excursion trains of ten to fourteen cars to cross the bridge on

a summer Sunday. Crossing the Kinzua Viaduct by train was considered

a great thrill. However, Kinzua excursions were memorable in other

ways. It is said that train butcher would frequently empty drinking

water containers prior to start of an excursions, then sell salted peanuts

on their first trips through the cars. With everyone thirsty they

would do a land office business in lemonade, which had concocted in a barrel

in the baggage car of water, citric acid and half dozen lemons. The

gullible were targets for sharpers and gamblers who, despite the efforts

of railroad detectives, managed to operate the old army and shell games

to the loss and sorrow of those who had grown tired of examining the viaduct.

Occasionally, there was drunkenness and fighting and rare indeed was the

excursion train that failed to have its tender utilized as a beer cooler.

The Bridge House, a hostelry and the dance pavilion situated at the end

of the viaduct operated by a man named Lewis did a land office business

at exorbitant prices.

Adventurous excursionists would often try their skill at climbing the

structure. Usually, they were hailed down by the bridge tender before

they found themselves in trouble or had to be helped down from the ironwork.

However, the bridge inspector would often thrill the excursionists by climbing

the viaduct with his son on his back.

Some idea of the popularity of the Kinzua excursions was more than sufficient

to offset the $167,000 cost of the original structure. The last excursion

took place shortly before America's entry into First World War.

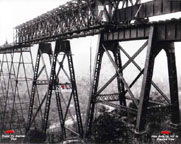

Replacement of the original viaduct was necessitated not by any defect

in the structure but rather by an unexpected and sudden increase in the

weight of locomotives and rolling stock. After only 18 years of service

it was necessary to replace the first Kinzua Viaduct with a newer and stronger

structure.

The second and present Kinzua Viaduct is of identical overall dimensions

with the first bridge. It is, however, designed to accommodate double

headed, ?consolidation? locomotive with loads of 35,000 pounds per axle.

Traffic over the original bridge was halted May 14, 1900 and resumed

over the new structure September 25. Reconstruction did not begin

until May 24 and the last girder was placed September 6. The work

was accomplished in four months by between 100 and 150 men working 10 hours

a day. This despite a week long strike; the speech of a presidential

candidate whose private car was brought to the site over the Kushequa Railroad

which had been built in the 1890?s to run beneath the viaduct; and a forest

fire which originating beneath the viaduct, swept unchecked through the

timber slashings to consume two communities before being brought under

control at the edge of a third town.

The reconstruction, directed by CAW. Buchholz chief engineer of the

Erie and executed by the Elmira Bridge Company, involved the removal of

3,105,000 pounds of mild steel in the new viaduct. The work proceeded

from both ends where storage yards were located. It was affected

by the use of two 180 foot timber travelers, each a complete Howe truss,

16 foot deep. These spanned three towers. The middle tower

was demolished and reconstructed. Then the traveler was moved to

effect the reconstruction of the next tower. The work moved at the

astonishing rate of 500 feet a month. The highest tower and its adjoining

spans were demolished in one day. Rebuilding of the same tower and

the adjoining spans required seven and one half days. The water boy,

Andy Kinzua Stauffer, enjoyed the privilege of removing the first bolt

from the old structure and of driving the final golden rivet in the new

viaduct. Thirty seven miles of rivet rod were used in assembly.

Supporting posts of the new structure were of plate and lattice construction

and measured 24 by 30 inches. The latticework spans of the old structure

were replaced by girders five and one half feet deep at the tower tops

and six and one half feet deep in the spans between the towers.

Engineer Chanute

Octave Chanute, for whom the U.S. Army Air Field in Illinois was to be

named, served in an engineering capacity on both structures. It was

he who worked out the problem of wind stress on the second structure designing

it to withstand a pressure of fifty pounds per square foot when unloaded

and thirty pounds to the square foot when loaded. The smaller figure

for the loaded bridge is due to the fact that pressure of thirty pounds

to the square foot would be sufficient to blow a train from the structure.

Wind is a very real factor in the Kinzua valley and within a year after

the second viaduct was erected it was blown two and seven eighths inches

out of line. At times the wind has been strong enough to relieve

staked gondolas of their tanbark loads and to unroof boxcars. Trainmen

will tell of being unable to stand upright on the deck of the viaduct in

a high wind and even on apparently calm days painters have found it difficult

to work.

Since its erection the viaduct has been painted on an average of once

in every seven years. The original stone piers were encased in concrete

between 1907 and 1933. These with the abutments bear the chiseled

initials of generations of visitors.

The present Kinzua Viaduct, like the original, still serves as a tourist

Mecca. Thousands still visit the Kinzua every year and hundreds will

be attracted to it on a sunny, summer, Sunday afternoon. Its plate

and lattice legs have challenged climbers of both sexes. Some have

succeeded in reaching the top; others have become faint hearted, ?frozen?

to the structure and have had to be assisted down. However, the outstanding

feat of balance recorded is that of the two young men who in 1901 mounted

the cap strips of the guard railings and keeping abreast crossed the viaduct

on a four inch plank 305 feet above the Kinzua Creek. There are,

too, records of two other individuals who have accomplished this feat?

of nerve and balance.

The lore of the viaduct is studded with legend. Most appealing

of all the stories is that which has to do with buried treasure.

Within sight of the Viaduct lies $40,000 in gold and currency buried in

glass containers by a bank robber near the turn of the century. To

date the loot has not been recovered.

The Kinzua has been surpassed in height by other viaducts. It

is eclipsed by the 336 1/2 foot Loa Viaduct in Chile, by the 335 foot Gokteik

in Burma and by the 362 foot Pecos River Viaduct in Texas. However,

the Kinzua is believed today to be the second highest viaduct on the North

American continent and it is doubtful if any viaduct in the world of its

type exceeds it in both length and height.

Today the Kinzua remains one of the great viaducts of the modern world.

Despite rumors and fantastic flights of fancy to the contrary, it has not

collapsed nor has it been destroyed for the benefit of the motion picture

cameras in a super colossal head-on collision of trains assisted by a few

sticks of dynamite to make a Roman holiday for Hollywood.

Bulletin

After the preceding pages of the story, ?Tracks Across the Sky,? had been

made up, the author came upon some sidelights and sent them on to us.

He says: ?J. Belmont Mosser of St. Mary's, Pa., who has just retired

as president of Kiwanis International, sold peanuts and popcorn on early

Kinzua excursions.?

Quoting Attorney Thomas J. Hurley of Gary, Ind., he writes:

?There may have been others walked the length of the viaduct

atop the handrail, but, believe it or not, two of the youthful and perhaps

foolhardy adventurers who did it were yours truly and an old friend, Jack

Flaherty. This was a day or two after the work was completed.

We discussed doing the stunt at the same time with a piece of rope between

us, he on one side and I on the other, to insure against one falling; yet

we abandoned this as too sissified. But we were accustomed to working

great heights and were young, strong and of steady nerve.?

About the Author

?I'm on the Era roster as an extra engine pumper and put in shift more

and then taking care of a couple 3100s at Clarion Junction which includes

coaling, sanding, cleaning fires and shoveling cinders in weather fair

and foul. I've spent a goodly portion of my life along the Erie living

at Jamestown. I was graduated from high schools and Meadville where

I could see the Erie yards and shops from my fraternity house windows.

I've received an education at Dunkirk, N.Y. Business Institute, Allegheny

College, Boston University Graduate and Theological Schools and done special

work at Yale and Emerson College of Oratory. I've served two pastorates

of the Methodist Church, Waterford and Johnsonburg, Pa. Have an avid

interest in photography, writing, stamp collecting and have 200 hours as

a pilot.?

Gordon Ruoff Collection

|

1883

Kinzua Bridge

1883

Kinzua Bridge 1900's

Kinzua Reconstruction

1900's

Kinzua Reconstruction 2000

Kinzua Bridge

2000

Kinzua Bridge