chief contractor for Frank Lloyd Wright's Falling Water

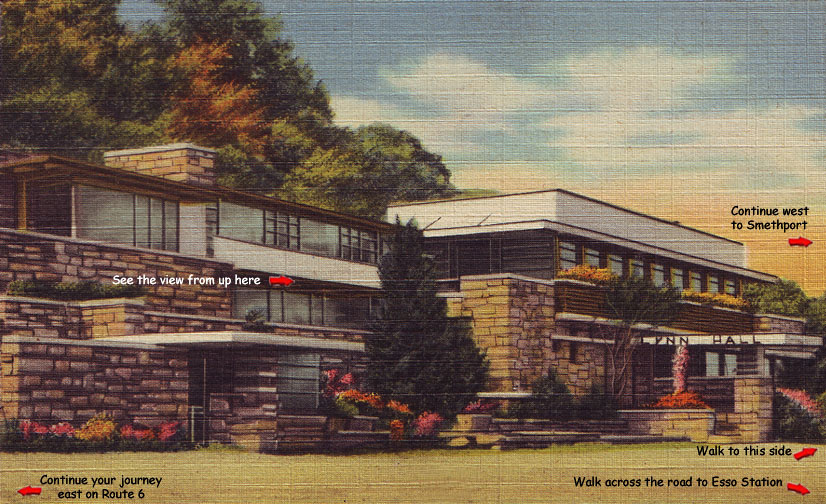

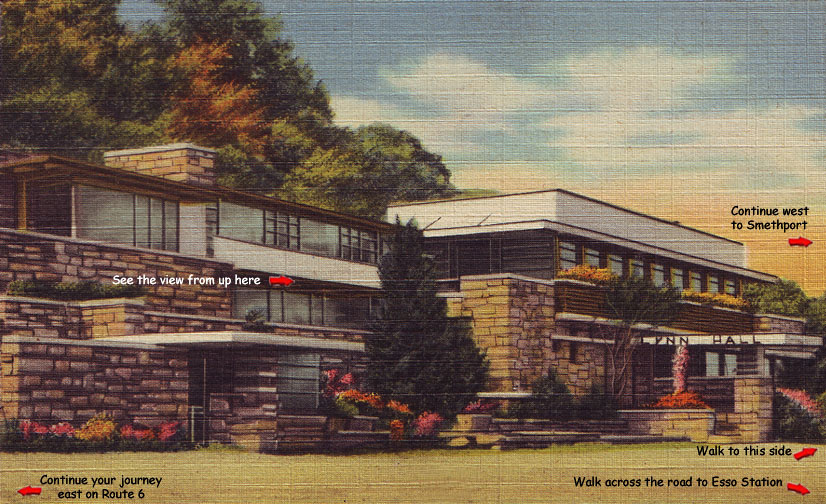

Lynn Hall as it appeared druing the 1940s

photo credit: John G. Coleman Collection

View Lynn Hall, Port Allegany in a larger map">see Lynn Hall on Google Maps

View Lynn Hall 2005 A.D.

Welcome To Lynn Hall: Builder Walter J.

Hall

chief contractor for Frank Lloyd Wright's Falling

Water

Lynn Hall as it appeared druing the 1940s

photo credit: John G. Coleman Collection

View Lynn Hall, Port Allegany in a larger map">see Lynn Hall on Google Maps

View Lynn Hall 2005 A.D.

|

Port Allegany

Man Helped Build Fallingwater A Port Allegany man who built

a hillside inn there was involved with architect Frank Lloyd right in

building the world-famous Fallingwater house at Bear Run. |

Far

from FallingWater,

http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/s_172008.html December

28, 2003 High on Route 6, the road to Port Allegany, (Pennsylvania), sits an exquisite show of stonework, a sprawling, flat roofed restaurant that was built by hand by a man who near-missed history. It was wonderful, once. There was a piano, an indoor trout pond and a fireplace that could fit a 6-foot log. Big window offered a view of the valley below. Across the road, on the hillside, in the style of the Hollywood sign , were the letters that read “LYNN HALL”--- on the boards so big you could see them clear across McKean County. That glory, like the man who imagined it, is long gone. The rooms are cold now, and cluttered, littered with car seats, caulk tubes, tarps, and old tools. The windows have frosted over. The ceiling above the entry has collapsed. Upstairs, in the old architectural office, a tree tore through the roof, bringing in rain that buckled the floorboards. Yet the building, all but abandoned after the cook left, owing rent, and the architects shop closed, and a second wife won all rights to it all, only to ignore it, letting the boiler to burst and water drip in, still manages to look as familiar as it is forgotten. The flat roof, the stone floors, the long row of windows with the booths below-all are the trademarks of Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect who built Fallingwater, the Fayette County home that is among the nation's best known. Every few weeks, then, when someone pulls up to the pump house and asks Ray Morton Hall, a retired pilot, for a look at “the Frank Lloyd Wright building,” Hall tells them the truth: that his grandfather, Walter J. Hall built this place, on a lonely road not far from the New York border, and then went on to build fallingwater, too. “ A Joint Of His Own” locals know route 6 as the Roosevelt Highway, part of a patchwork tack that ties Cape Cod to Long Beach, Calif. Port Allegany's portion was still being built when Walter Hall bought his 55 acres of pasture land. The road going there was dirt then. Hall was a no dollar eyed speculator. His wife had died, and his home life had disappeared with her. “he pretty much assumed he was going to spend the rest of his life alone, in boarding houses,” says his grandson, now 65 himself. “he figured he might as well have a joint of his own.” He started Lynn Hall, named after his mother, in 1934. The building first appeared on the local tax rolls years later. To Ray Morton Hall, who lived in a wing of the building as a boy, before moving to the smaller pump house, those dates are essential details. Fallingwater, he knows, was not designed until 1936. The two buildings - one renowned, the other neglected, - are undeniably tied, even to an untrained eye. The designs, from the roofs to the windows to the walls themselves, with jutting stones to serve as built in shelves, are entwined. That's why so many pull up to Ray Morton Halls drive. Each time he smiles, stirs his coffee, and sets them straight. It's the old chicken-and-egg question, he says. And the dates say his building came first. “People think it's a Frank Lloyd Wright building,” he says. “But it's actually the other way around. Fallingwater could have been a Hall building. It is, in the sense that Hall got it built. Wright's client, E. J. Kaufmann, paid his $50 a week-and $25 more a week for every time he came in under cost. Kaufmann's son, Edgar Jr., took credit for bringing the men together. On a drive to buffalo, to eye some of Wright's other work- Darwin Martin house, maybe- he saw the Lynn Hall stonework and alerted his father of the opportunity. Or so he said. Franklin Toker, the University of Pittsburgh professor who wrote “Fallingwater rising,” a richly detailed new history of the Bear Run home, believes another man brought Hall on board. After his book was printer, Toker heard from a niece of Earl Friar, who managed a farm at Taliesin, Wright's Wisconsin compound. His letters, she said, show that before that, Friar had worked for one Walter J. Hall . A Question Of Stolen Silver At Bear Run, the man wrestled with Anaean egos. Wright, when he bothered to appear, dressed eccentric, with his hat and cane and the occasional cape. Hall fashioned a cloak of his own, and a head-wrap he tied at the temples. Kaufmann quarreled with both. He sent a subordinate, Carl Thumm, to monitor their progress. Thumm was the one who approved, without Wrights knowledge, the use of extra steel reinforcements in the home's soaring cantilever, which cracked anyway. “Thumm would come on Sundays,” says Rudy Anderson, a young carpenter Hall brought from Port Allegheny. “He'd go over all the work I had done the week before, that pretty much took care of my Sunday afternoons.” Kaufmann's son called Hall “rough hillbilly contractor” when he spoke to Donald Hoffman, the Kansas City architecture critic who wrote “Fallingwater: The House And Its History.” But Hoffman came to his own conclusion. “Reading Hall's letters,” he says, “it struck me that he was quite on the ball. It didn't make any difference where he came from. He knew what he was doing. Wright was lucky to find him, actually.” “Hall may have been rural,” he says, “but he was straightforward, Certainly more so then Wright. Wright was the holy devil when things didn't go his way.” At Bear Run, they rarely did. The architect's designs often fell short, with measurements off or missing altogether. Hall, who worked for 40 years before coming to Bear Run, made changes as he went. That infuriated Wright, who vented in a letter penned in August of 1936. Ray Morton Hall keeps it in a Ziploc bag. “My Dear Hall,” Wright wrote. “I guess I took too much for granted when I called you on the Kaufmann house. Probably you have always been your own boss, never worked for and architect and never heard of ethics.” Cleary the work wasn't going well. Wright was under pressure. “I have put to much into this house (even money, which item you will understand)to have it miscarry by mischievous interferences of any sort,” he wrote. “the kind of buildings I build don't happen that way. Several have been ruined that way, however, and this one may be one of them.” Ray Morton Hall's wife, Rhonda, looks up from the table, where she has been grading papers. “Walter and Wright were meant for each other,” she says. “They were both irritating. Kaufmann, ever the salesman, was smoother. In his own letter to Hall - this one, from 1940, the grandson has framed-he praises the man's master craftsmanship. Then gets to the point: “At the time you moved into the stone house early last spring we had a couple, if you remember, Mr. and Mrs. Waktor, who was living there. Mrs. Kaufmann bought a complete list of kitchen utensils for them to use in the house.” “These utensils has entirely disappeared, and Mr. Lewis Ohler claims that you came and got them. He was under the impression that you purchased them.” Then, diplomatic to the end:” I am trying to locate them, and you might be able to help me by telling just what took place.” Ray Morton Hall laughs at the accusation, “you know,” he says, “we probably ran the restaurant with that stuff.” An A-list Attraction Back home, the Bear Run project behind him, Walter Hall built his restaurant lodge in a A-list attraction. He stocked the pond with fresh trout. He polished the 117-year-old Steinway. He circulated, working the dinner crowd with the joy of a man no longer alone. “That man liked to mingle,” says Rudy Anderson, the carpenter Hall had hired for the Kaufmann job. Anderson, now 87, took his parents to Lynn Hall for their 45th wedding anniversary. His wife ordered the fish, which came to the table with the head still attached.The dining room was crowded back then. Companies held their Christmas parties at Lynn Hall. Wedding parties filled the ballroom upstairs. Guests stepped out on the terraces for a breath of fresh air. Those days passed to fast. Hall, a teetotaler, did not allow a drop of liquor in his building. That, and gas ration during world war II, crippled his business. The route 6 restaurant was suddenly too far from the Buffalo, NY, billboards that advertised it. Hall died in 1953. The cook quit soon after, owing rent, and the restaurant closed for good. The dining room upstairs is a mess now, a mix of paint rollers, ladders and shop-vacs, with an easel and some extra chairs thrown in. the entire floor was under water once. “It ran through here like you'd turned on a garden hose,” Ray Morton Hall says. The kitchen was worse. There were holes in the ceiling Hall could have dropped a jeep through. The ballroom upstairs has been walled into offices. Hall's son, Raymond Viner-Ray Morton Hall's father - made that his architecture shop. From there, he designed several of the area's high schools, and a PPG Fiberglass plant for O'Hara Township, Allegheny County. “There was a lot of work coming in,” says Preston Abbey, who worked at Lynn Hall until 1953. “We were never wondering what to do.” The men worked at wide tabled set against the long wall of windows. “you had a beautiful view of the valley,” Abbey say. “It was quite nice.” The tables are still there. Ray Morton Hall pulls a tarp off the top of one and pages through several sheets of blueprints, many of them taped in places, the color bleached. All the prints are from 1936. From Fallingwater. “The Home's Crown Jewel's” A low door near the back of Lynn Hall, where the building snug into the hillside, opens into what was meant to be the first guest room. The floor is still dirt. Walter Hall never got to it. His grandson has made this his workshop. Hand tools hung over a tinker's bench. Cut lumber is stacked to one side. A table saw sits in puffs of fresh sawdust - the same saw Walter Hall used at Fallingwater. Ray Morton Hall always thinks of his grandfather here. He was close to him; as close as he was to his father, maybe. It breaks his heart, seeing this place fall apart. “You can see what it once was,' he says. “And you can see what it could be again.” His options are limited, however. Port Allegany, a town of just 2,300, has little use for Lynn Hall. The economy is stunted. The closest hospital has just 34 beds. The state police barracks is an hour away. “Our community is a ghost town,” Hall says. “The industry has withered. Were down to a milk-the-cow situation.” The western Pennsylvania Conservancy, which maintains Fallingwater, charging $10 for tours, has not moved to protect Lynn Hall, Fallingwater Director Lynda Waggoner has never been there. The Wright connection might be Hall's best bet nonetheless. That's what brings people to the property now. With them, he argues his grandfathers standing, positioning him - and his last home, for history. Still, his chicken-and-egg analogy misses an issue. though Walter Hall started Lynn Hall long before Fallingwater took shape, he clearly was influenced by Wright - if not at Fallingwater, then at the Martin House, or at Taliesin. Both buildings were well known, and widely publicized. Hall, who had once glimpsed Wright in Buffalo, would have known both. Raymond Viner Hall even applied for a fellowship at Taliesin. Later, he flew his entire staff to Philadelphia to view an exhibit of Wright's work. Wright's standing is assured, of course. The American Institute of Architects has called Fallingwater “the best all-time work of American Architecture.” Ray Morton Hall cannot compete with that. “The Wright mythology is established,” he says. “It's set.” His grandfather's contributor's get much less credit, when they are acknowledged at all. “I don't think there was much influence for Hall back to Wright,” Donald Hoffman says. “Hall's letters show that he more or less worshipped Wright. He put up with an awful lot of nonsense.” His stonework, though, may well have changed the feel and flow of Fallingwater's floors. “I'm quite sure Wright got that from Walter Hall,” Franklin Toker says. The walls, too, owe much to Hall. “The stonework at Fallingwater is one of the home's crown jewels,” Toker says. “It's the most lyrical stonework in America. It mesmerizes you. It appears to be straight out of Nature. “Nobody had ever achieved that before,” Toker says. “Not Wright, and not Walter Hall.” The men parted ways after Bear Run. Hall wanted to pursue other projects, Lynn Hall among them. His true influence at Fallingwater may never be known. “It's not simple at all,” Toker says. “It's a little uncertain, like a Rembrandt, where the student starts it but the master goes over it later. And it's foolish to pronounce on that.” Ray Morton Hall is left, then, with the few curious people who stop to talk, always asking the wrong question. He has a Wright letter, his blueprints and his grandfather's saw. He has a cold building he cannot fully insure. And he has the nagging sense, now that he is older, that Lynn Hall, where so many other buildings were born, one day will be no more that a historical footnote, sure to be forgotten |

Which

Came First? |