SEVEN

MEN EARNED PERFECT SCORES

The Bicycling World

New York, USA

Thursday July 10, 1902

Boston-New York Endurance Contest the Biggest

Event in Years and Proved an Eye Opener- Awakened Great Interest in Motor

Bicycles- The Men who Competed and how They Fared.

THE MEN AND MACHINES THAT WON THE AWARDS

GOLD MEDALS

George M. Holley, Bradford, Pa., 2 1/2 h.p. HOLLEY

George W. Sherman, Brooklyn, N.Y., 1 3/4 h.p. INDIAN

N.P. Bernard, Hartford, Conn., 2 1/4 h.p. COLUMBIA

George M. Hendee, Springfield, Mass., 1 3/4 h.p. INDIAN

O. L. Pickard, San Francisco, Cal., 1 3/4 h.p. INDIAN

L. H. Roberts, Waltham, Mass., 3 h.p. ORIENT

William B. Jameson, Waltham, Mass., 3 h.p. ORIENT

BLUE RIBBONS

W. T. Marsh, Brockton, Mass., 1 3/4 h.p. MARSH

F. W. Tuttle, Hartford, Conn., 2 1/4 h.p. CLEVELAND

RED RIBBON

Emil Hafelfinger, New York, N.Y., 1 1/2 h.p. ROYAL

YELLOW RIBBON

Joe Downey, Brockton, Mass., 1 3/4 h.p. MARSH

It may now be said that the public and the motor bicycle are fairly acquainted

one with the other. While they have known each other in casual fashion

for some little time, the formal introduction did not take place until

the 4th and 5th of the current month. The Metropole Cycling Club, of this

city, played the part of introducer, and played it well. Its Boston-New

York endurance run on those dates was the occasion of the introduction,

and the trail of interest and publicity which the event created, and which

radiated in every direction through the public prints, in ample evidence

that the hopes of the promoters were more than justified.

The contest demonstrated thoroughly the practicability and reliability

of the little self-propeller on give and take roads, under conditions

both favorable and unfavorable, and as fully proved that the man is no

less a factor than his machine. Skill and expertise counted for much.

It was a test full of accident, incident, instruction, and color.

Of 32 entries, 31 started from Copley Square, Boston, on the morning of

the 4th. The solitary non-starter was on the ground the night before,

but for cause was then and there summarily discharged and his bicycle

taken from him by his employer, who also was in evidence. Frank Kellogg,

of the Massachusetts Bicycle Club, was the starter who sent the men away

in pairs at intervals of one minute. C.A. Persons was the first man to

be given the word, at 8 o’clock sharp. H. J. Wherett, the last one,

did not leave until 8:59, forty-three minutes behind his scheduled time

of departure, and long after the crowd of spectators had frittered away.

Of these spectators the most notable was Frank W. Weston, the “father

of American cycling,” who twenty-five years before had introduced

the then bicycle to the public and gave it the life, purpose, and prominence

that led ultimately to universal popularity and, in the natural process

of evolution, to the motor bicycle.

As lined up the contestants made a picturesque gathering. There were tall

men and short men, thin men and men not so thin, and one who cam close

to being fat, Jameson, of Waltham, short, stout and with a round, good

natured face. It was their diversity of garb, however, that formed the

picture. There were the Marshes in leather coats, caps and leggings; Seaman

in a suit of blue “jumpers”; Beeber and Rogers in military

khaki; Holley wearing street clothes, a cap and starched shirt and collar;

Persons and Roberts in Norfolk blouses; others wearing ordinary bicycle

costumes and caps, and one tall youngster, Burnham, of Waltham, attired

as if for a ride around the block, street clothes, starched collar, flat

brimmed straw hat and all; he even did not secure his long trousers with

trouser clips.

This same Burnham was the character of the run. His conduct was as odd

as his clothes. He apparently knew no one, and sought to make no acquaintances;

he rarely spoke. But the boy knew how to handle a motor bicycle. ON the

first day he scored his 500 points with plenty of time to spare. He reached

Hartford early, and as fresh as if he had ridden 26 miles instead of 126,

quietly deposited his machine in the control, and then disappeared and

was seen by none until the next morning. His performance, coupled with

his oddity of dress and action, was noised about, and overnight he became

the wonder of the run. The Marsh contingent were in ecstasies, and were

in a mood to “do the handsome” for the unknown. He was not

seen again until the next morning, a few minutes before the start. He

reached Meriden, still with a perfect score to his credit, and there the

“wonder” of two hours before developed a deep streak of chromatic

yellow. He quit suddenly and without cause. His machine was working splendidly,

and he himself said he was not tired, but no amount of persuasion could

induce him to go a yard further. When his quitting became known to the

admiration of the day before quickly changed to curses of condemnation.

Most of the other contestants were made of sterner and less eccentric

stuff. They pressed on until physical or mechanical troubles forced them

to stop. Seaman, of Mineola, L.I., Broke off his right crank and a portion

of his crank shaft in starting, but nevertheless covered the 81 miles

before quitting. It was tire and coaster-brake troubles that caused most

of the early retirements, Root and Wherett, on Strattons, being the first

and chief sufferers from motor troubles. The former attempted to drive

his motor with a long chain direct from a rear sprocket to the gear wheel,

and did not get five miles outside of Boston. Wherett’s motor also

went wrong soon after the start.

It rained the night of the 3rd, and in consequence the usually fine roads

out of Boston were in treacherous shape. But, despite their slipperiness,

the men took chances, most of them riding as if fast time, instead of

a steady 15 miles per hour, was the object. As a result the laughable

spectacle was presented at the first control, South Framingham (23 miles),

of 28 of the contestants grouped within a few yards of the green flag

denoting the control. They refused to actually pass the flag until their

15- mile time limits expired. This procedure ensued with decreasing numbers

at practically all of the succeeding controls.

Even before the contest started there were stories that the two men from

the West, Beeber and Rogers, were subjects of solicitude on the part of

not a few of the others. Beeber and Rogers came direct from the Mitchell

factory, the last mentioned having only recently come from abroad, where

he had earned a reputation by piling up not a few motor bicycle records.

They had ridden over the course the reverse way, going form New York to

Boston, and the experts from the other factories seemed to view them as

objects of particular interest and for particular attention. It soon became

known that the two Westerners, with Roberts and Jameson, the Orient pair;

Pickard and Sherman , of the Indian tribe, and George Holley, were each

concerned about the other. The four Hartford men were also factory experts

but were under the direction of a manager, and they had little to say

for themselves, but heir eyes were supposed to be open. The result was

that one or the other was always in front. Usually they were in pears,

each shadowing a particular one of the others and making sure that he

did not keep more than a few yards away. Some fast work, which ended only

when the green flags came into view, was the outcome. The men were experts

in every sense of the word. The way they handled their machines was a

revelation. They took all sorts of chances on all sorts of roads, and

when all was over even Pickard, on the most daring, was full of praise

for Holley and Bernard particularly.

Since the affair some of the men have been given to figuring their “actual

riding time,” and while it may be a agreeable pastime it is not

authoritative and serves no purpose. The men themselves clocked the times

on which they base their “records.”

Unfortunately for all, Beeber and Rogers were among the first to reach

trouble. Rogers was bowled out by a big stone beyond South Framingham,

which crushed his front wheel and threw him hard. He sustained a cut to

the bone on one arm, and could not continue. Press dispatches afterward

stated that he had been carried to a hospital, but these were untrue.

He came by train to New York, arriving in time to see some of the survivors

finish. Beeber came to grief soon after his mate. His tire punctured and

coaster-brake went wrong, and after he had repaired things news of Roger’s

accident reached him in exaggerated form, and he spent some time in trying

to locate him. Being unsuccessful in his quest, he went on, reaching Springfield

after the control had closed. He remained there overnight, and early the

next morning made an effort to reach Hartford on his bicycle, but rain

during the night had converted the road into a quagmire, and the quagmire

won. The other Mitchell entries, Mankowski and Alimen, gave rare exhibitions

of pluck and road endurance. The former, an individual entry, had been

riding a motor bicycle but ten days. He had trouble on the slippery roads

out of Boston, but reached Warren but 25 minutes late. After that he had

several bad falls, and reached Springfield hours behind his schedule.

Nothing daunted, h e pushed on in the dark, arriving at Hartford minutes

after midnight, having walked some of the 26 miles from Springfield. The

next morning he was groggy, but still game. He again ran into trouble

after leaving Hartford, and had more tumbles. He bent his spokes several

times, and finally arrived in New York at 9 o’clock, with his muffler

tied on, his mixer loose and rattling, and his frame out of true. Alimen’s

experience was much the same, save that a puncture added to his woe. He

reached Hartford after dark with one trouser leg rent from top to bottom,

and came into New York five minutes after Mankowski. Falls which bent

his cranks and ripped a dozen spokes out of one wheel, and a heavy rain

squall had caused much of his delay.

View

the Summary Showing Standing of Each Rider at Each Control

Of the Indian triumvirate Hendee,

probably the heaviest man in the run, was the chief sufferer. He sustained

four falls, two of them bad ones. On the first day he ran suddenly into

a gulley after crossing a railroad track, and was thrown heavily, cutting

his face and tearing his rousers. At Bridgeport the next day he continued

and a ajdist and was almost put out of the running. Despite his accidents,

however, he reached all controls witin his time limits and scored the

coveted 1,000 points. Fortune and foresight favored the Indians. They

were the only men to carry an extra supply of gasoline. It was carried

in canteens slung across their backs. Once when Hendee fell he ripped

his gasoline tank and spilled the fluid, and, as luck would have it, at

the very moment an itinerant tinker drove up, soldered the hole in the

tank, and with his canteen of gasoline at hand Hendee lost little or not

time. On another occasion Sherman fell and broke a crank, and again fortune

smiled through the cloud; the accident happened directly in front of a

repair shop.

The Orient men met with little in the form of either accident or incident.

Jameson suffered some slight belt trouble; that was all.

The Marsh contingent had a succession of hard luck. Nearly all of the

machines were new ones that had not been ridden until the day preceding

the race. (indecipherable line) device with which the makers are experimenting.

The men did not arrive in Boston until late the previous night, and at

least two of them started in the contest the next morning without having

had breakfast. These two A.R. Marsh and Robert Halshall, were taken sick

at Worcester and forced to quit. Of the others Jenkins, Brown, Hoyt, and

G. L. Marsh were put out of the running by the breakage of their coaster-brakes,

Hoyt breaking a second one after having it substituted for the damaged

one at Worcester. Lane ran into a telegraph pole on the second day, and

was placed hors de combat. W. T. Marsh came through after a petty trouble

near Worcester that delayed him just long enough to keep him out of the

gold medal awards. Joe Downey, the other Marsh survivor, had a deal of

worry and lost many valuable minutes the first day by thoughtlessness.

He carried an extra tank of gasoline and foolishly fed the fluid through

a length of rubber hose. The gasolene, of course, ate the rubber, and

in due time Downey’s gasoline supply was choked, and he had no easy

time clearing the tank. He rode into Hartford disgusted and swearing at

himself.

The American Cycle Mtg. Co.’s quartet, the four Hartford entries,

were a competent lot. They knew their machines like a book, and knew how

to handle them. Bernard was easily the “star.” Save for one

puncture and the breakage of a chain link, due to his use of one that

was a size larger than the others, he went through without a skip, fall,

or mishap, and was one of the freshest men at the finish. O’Malley

had a puncture between Springfield and Hartford which let his wheel down

on a stone and tore off his muffler. The puncture was a bad one and could

not be repaired. O’Malley filled the tire with sand and made a game

effort to reach Hartford on that makeshift. The effort tore twenty odd

spokes out of his rear wheel, and he finally reached Hartford afoot. The

next day he had sparking troubles and was not heard from after Bridgeport.

Russell, one of his mates, had the distinction of being the only man to

be disqualified. He fell and broke a pedal and handlebar near Hartford,

and then permitted himself to be towed for some distance. His disqualification

was due to the honorable and sportsmanlike instincts of Arthur L. Atkins,

manager of the Columbia Factory. Russell reached the Hartford control

on time, and as none knew of his having been towed he was credited with

a perfect score. He said nothing to the officials about his violation

of the rules until an hour later, when Mr. Atkins compelled him to admit

and report his offense. Only those who are in position to know the trade

rivalry that existed and of Atkins’s keen interest in the event

and its outcome can fully appreciate his honorable action.

The two Holleys in the run were ridden one by George M. Holley himself,

the other by E. L. Ferguson. The latter located a short circuit in the

handlebar and then made a makeshift circuit by carrying the wire in his

hand and against the handlebar. Later he attached the wire to the screw

securing the spark lever, and when he suddenly encountered a gully in

the road could not break the connection quickly enough, and was thrown

headlong into the woods at the roadside, where he lay stunned for some

forty minutes. He managed to reach Worcester and being badly “done

up” he therein and as secretary of the promoting club joined the

chairman and the referee and followed the run by train and checked the

checkers at the different controls. Holley himself admitted some belt

slipping. Beyond this triviality nothing happened. His control of his

machine was superb. Neither mud, dust, sand, ruts, hills nor anything

else fazed him. Once when another rider complained of the roads Holley

smiled.

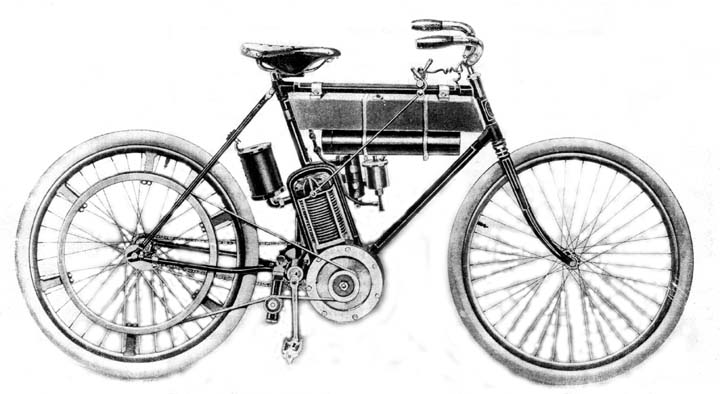

From Left to Right: Holly, Pickard, Roberts,

Bernard, and Checker Oatman, at the New York Control. |

“Why ,they are like boulevards.”

He exclaimed in his quiet way. “I wish we had them out our way.”

Holley had not a fall and was always near the front. The only chance he

did not take was that of disqualification. There was sharp rivalry for

the credit of being first at the controls, and at Hartford Pickard, who

arrived first, Jameson, Roberts and Henshaw were all cautioned for overspeed,

and the penalty would have been inflicted but for a misunderstanding as

to the position of the control flag, which entitled the men to the benefit

of the doubt. Holley came in with the two Orient men, but he had so timed

himself as not to require the warning. The second day was practically

a Holleyday. He was in front all the way, and reached New York ten minutes

in advance of the next man, Bernard. There has been some controversy on

this point, but a Bicycling World man, stationed at the turn a half mile

from the finish, checked and timed the leaders at theat point, as follows:

Holley, 5:01p.m.; Bernard 5:11p.m.; Roberts and Jameson, 5:12 p.m.; Pickard,

5:13 p.m.; Sherman, 5:32 p.m.; Hendee, 5:36 p.m.; Tuttle, 6:01 p.m.

The first four were ahead of their scheduled arrivals, and seated themselves

in Central Park until they were free to arrive at the control across the

street without penalty. A photographer induced them to come into the station

to pose for their pictures, an act that came near spoiling Roberts’s

clean score. The others were safe at the time, but Roberts had a few moments

to kill and thoughtlessly joined them, crossing the threshold just fifteen

seconds outside his unpenalized limit.

Of the Royal entries, Hafelfinger gave a splendid account of himself.

He used the smallest motor, one of the scant 1 1/2 h.p., but he also employed

a two speed gear, the only one in the run, and with it was able to climb

practically every hill, on some of which far more powerful motors balked.

He scored 100 points on every control save the last one of the first day.

On that stretch he ran out of gasoline, had a fall which bent his brake

and hurt his leg. Further on he became so parched he accepted the invitation

of some good natured Germans to help them dispose of a keg of beer and

dallied too long. Ten miles outside of New York he punctured, and after

riding some distance on his rim found a repair shop. The repair held until

he came within twenty yards of the finish, when the tire again went flat.

C. A. Pearsons, the other member of the Royal family, had made four perfect

controls, when unknowingly his leg touched and opened the tap of his lubricating

oil, which simply flooded his entire motor and created a short circuit

that he could not locate. His enforced abandonment of the urn left him

almost broken hearted.

The only Auto-Bi in evidence, that ridden by Henshaw, behaved beautifully

and had a clean score up to Meriden, where the fork-crown broke.

The weeding out process was interesting. Three men failed to reach the

first control, 23 miles. One fell out between the first and the second

Worcester (45 miles), and five between Worcester and Warren, 71 miles.

Between Warren and Springfield (100), where the worst roads were encountered,

there were but two failures. On the road to Hartford (126) two more joined

the ranks of the unfortunates, and one arrival was disqualified, making

fourteen failures on the first day.

On Saturday seventeen men started, and all reached Meriden (146 miles).

Between Meriden and New-Haven (166), two declared themselves out of it.

Between New-Haven and Bridgeport (186) none quit, and between Bridgeport

and Greenwich (220) the ranks were further thinned by two. The thirteen

who passed Greenwich reached New York (254 miles), and of these thirteen,

seven finished within their allotted limit, and earned perfect scores

of 1,000 points each, surprising even the promoters. All who survived

and failed to win gold medals will be awarded bronze medals commemorative

of the event, and presented by the Bicycling World.

The contest was scored on a basis of 100 points for each control or checking

station, of which there were ten. Each man was required to arrive within

prescribed limits, there being a penalty of one point for each minute

that he fell behind the slowest time allotted him. There was a penalty

of three points also for each substitution of gasoline tanks, lubricant

retainers, battery cases, cylinders, cylinder heads, crank cases, mixers,

mufflers, driving gears and spark controllers, each of which was marked

for identification before the start. On the machines that survived, however,

there were no substitutions, and, of course, no penalties were inflicted.

Of the thirteen survivors, seven, as stated, finished with perfect scores

of 1,000 points each, and thereby earned gold medals, denoting the highest

possible award, two others obtained blue ribbons for coming within 50

points of the winning score, one a red ribbon for earning within 100 points,

and one a yellow ribbon for being within 150 points of the leader’s

total.

The Metropole Cycling Club Committee in charge of the run were Will R.

Pitman, chairman; E. L. Ferguson, secretary; George W. Sherman, Henry

Van Ardsdale and Charles E. Miller.

The officers of the event were:

Referee, r. G. Betts, president, Metropole Cycling Club; starter, Frank

Kellogg, Massachusetts Bicycle Club; checkers, at South Framingham, Charles

f. Whyte; at Worcester, Lemont and Whittemore: ast warren, D. E. Graves;

at Springfield, W. E. Crowe, Massasolt Cycle Club; at Hartfor, H. W. Alden;

at Meriden, Wusterbarth Brothers; at New-Haven, Campbell Cycle Company;

at Bridgeport, William Stiff; at Greenwich, C. H. Minchin; at New Yhork,

Alderman Joseph Oatman, president A.C.U. of New York.

|